A new label for Asperger’s syndrome may help children get needed treatment. But early intervention is still vital.

Keagan Peterson’s first birthday party was a happy occasion, with cake, balloons and gifts, but his mom, Stephenie, couldn’t shake the feeling that something was wrong. Keagan, now 6, seemed to be suffering from a major sensory overload. “He didn’t want to touch the frosting on his birthday cake. He was greatly upset by the feeling of the grass on his feet. And I noticed that he wouldn’t sustain eye contact,” she recalls.

By age 2, he’d been diagnosed with Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD). But the diagnosis didn’t explain all of Keagan’s quirks: his habit of repeating words and phrases, his obsession with patterns or his penchant for gigantic violent meltdowns.

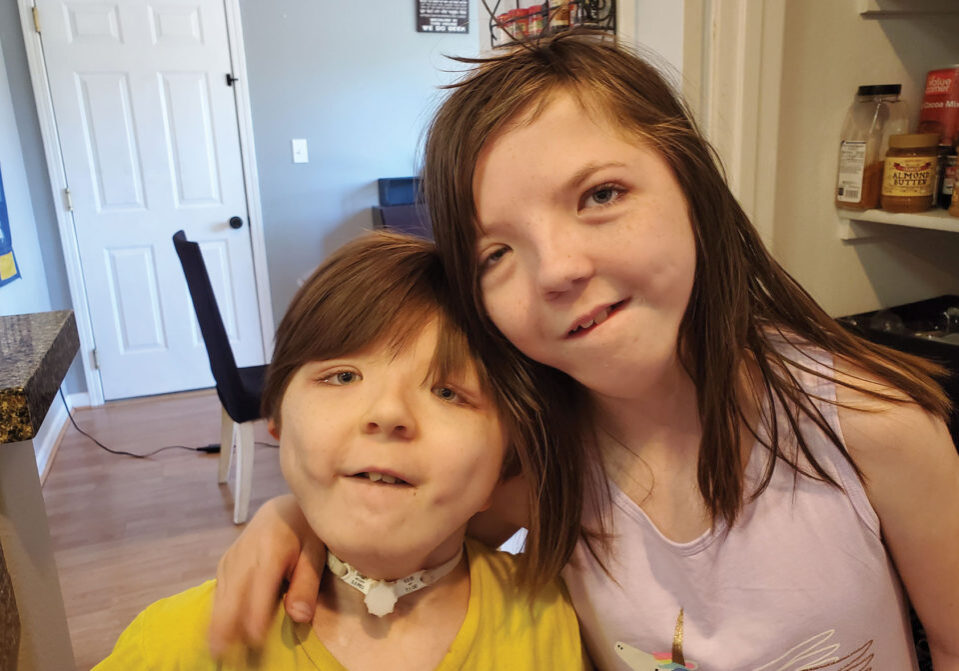

He was officially diagnosed with autism at 3, about the time his family moved from the Northwest to Dallas, Texas, where they now live. But his symptoms, such as his inability to read social cues, avoidance of eye contact, high intelligence, and advanced vocabulary, were more consistent with Asperger’s syndrome, one of numerous developmental disorders on the autism spectrum. Earlier this year, his 4-year-old sister Eden received the same diagnosis: high-functioning autism, or Asperger’s syndrome.

Two kids with three labels between them – SPD, autism, and Asperger’s – made life complex, and insurance paperwork was a nightmare. It’s a familiar scenario for families with a child (or two) on the spectrum. Because many spectrum disorders have overlapping symptoms, arriving at an accurate diagnosis and getting needed treatments can be a murky medical maze.

A new label

But it may be getting a little clearer. At least, that’s the hope of the American Psychiatric Association, which, in 2013, removed the diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). Under the new definition, Asperger’s is recognized as a form of high-functioning autism and is grouped under the autism umbrella, along with other familiar spectrum disorders like pervasive developmental disorder and childhood disintegrative disorder. The change could make it easier for those on the spectrum to get needed treatments, since certain states provide services for autism but not for related spectrum disorders like Asperger’s.

The DSM is the diagnostic bible used by mental health professionals, education providers, and insurance companies. Its language channels the flow of treatment resources, helping schools determine how to allocate special education funding and informing insurance companies’ decisions about coverage. Changes to its verbiage are a big deal, and not without controversy. This one sparked angry protest and impassioned petitions from Global and Regional Asperger’s Syndrome Partnership and the Asperger’s Association of New England.

And new research is stirring up more controversy by making the case that Asperger’s is, in fact, a distinct disorder. According to a study published in BMC Medicine, children with Asperger’s have different electroencephalography (EEG) patterns (or brain waves) than children with autism – showing that Asperger’s is not merely a mild form of autism, but an entirely separate condition with unique neurological implications.

Many health professionals acknowledge that Asperger’s syndrome has unique characteristics that differentiate it from autism: Individuals with Asperger’s don’t have the language deficit often seen in those with autism, are not intellectually impaired, and can have tremendous focus. These uniquely “Aspie” (a friendly nickname for those with Asperger’s) characteristics will continue to shape treatments and therapies for those with Asperger’s, even under its new “autism” label.

But regardless of how the disorder is labeled, early intervention is key to successful treatment. “While the brain remains plastic throughout life and new things can always be learned, the greatest plasticity is during the younger years,” says Stephen Shore, Ed.D., author of Beyond the Wall: Personal Experiences with Autism and Asperger Syndrome. So interventions like occupational therapy, speech therapy, and specialized social skills groups may have the greatest impact – and the best chance of positively shaping a child’s future – if they’re initiated during early childhood.

Sneaky symptoms

Asperger’s syndrome can be tricky to spot, particularly in toddlerhood, because it doesn’t cause speech delays. But symptoms often appear before age 3, and parents can pick up on the signs if they know what to watch for, says Gary A. Stobbe, M.D., program director for Adult Autism Transition Services with the Autism Center at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

Many times, children with Asperger’s begin speaking early, like Keagan Peterson, who knew hundreds of words before his first birthday. Children with Asperger’s can have large vocabularies, but may speak in a monotone or with an odd inflection. And they may be unable to match their vocal tones to their surroundings – they might not use a quiet voice at the library or at the movies, for example. They may lack physical coordination; movements may seem either stiff and stilted or overly bouncy, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Individuals with Asperger’s or high-functioning autism can struggle with “executive functioning,” or the ability to plan and organize, says Stobbe. Bigger challenges come during the school years, when children are expected to work on projects over several days and turn in homework.

Diagnosis drama

Ultimately, the precise name of the disorder may not matter much; a parent’s job remains the same, notes Stobbe. “Don’t let the diagnosis dominate your planning and parenting. Your goal as a parent is to provide an environment to help your child be happy and succeed.”

Life in a home full of Aspies has not been easy, says Stephenie. But it’s wonderful. “My kids are so smart, so funny, so amazing. And it isn’t like they are great kids in spite of Asperger’s. A lot of the amazing things about them are in part because of their Asperger’s.”

Symptoms of high-functioning autism (formerly known as Asperger’s syndrome)

- Monotone pitch

- Extensive vocabulary

- Restricted interests

- Lack of empathy

- Avoidance of eye contact

- Repetitive motions

Source: Stephen Shore, Ed.D., author of Beyond the Wall: Personal Experiences with Autism and Asperger Syndrome

Posted in: Special Needs

Comment Policy: All viewpoints are welcome, but comments should remain relevant. Personal attacks, profanity, and aggressive behavior are not allowed. No spam, advertising, or promoting of products/services. Please, only use your real name and limit the amount of links submitted in your comment.

You Might Also Like...

Wings of Eagles, Wings of Angels — Safety Nets For Families of Seriously Ill Children

When a family faces the challenge of caring for a seriously ill child, many emotional, physical, and financial stresses are involved. This type of strain can have lasting effects on […]

Celebrating Inclusivity At The Special Needs Carnival In Durham

For many people with disabilities, carnivals can be a stressful and anxiety-filled experience. Primarily geared toward “typical” community members, they often lack accessibility and can be a breeding ground for […]

Special Education Teachers Have Challenging, Rewarding Careers

Teaching students with special needs is a challenging, rewarding career. Special education programs are designed for students with intellectual, developmental, physical, or emotional delays which can place them behind their […]

COMPASS Offers Innovative Services for Adults with Disabilities

Living independently presents numerous challenges for adults with disabilities, including the management of medications, therapies and medical equipment, as well as navigating limited mobility, transportation barriers and safety concerns. The […]