In the summer of 1998, I returned home after a yearlong college study abroad program. One day as my mother and I were catching up, the conversation took an odd shift. “I need to tell you about a little medical problem I had while you were away,” she said.

“What problem?” I asked. I hadn’t noticed anything amiss with her health.

“Well,” she said, sounding sheepish. “Breast cancer.”

Over the next few days, the truth dribbled out. My mother had been diagnosed shortly after the holidays. She’d undergone two surgeries and radiation. And everyone else — from my younger siblings to the cantor at our church — had known for months.

My mom was no helicopter parent. But this decision was different: She wanted to protect me from worry and all its ramifications. As she put it, “We were afraid if we told you, you’d freak out and fly home.”

After learning the truth, I thought back to my time abroad, now shaded with the reality of my mom’s illness. While I was hopping on trains and practicing my Austrian dialect, my mother had been recovering from surgeries and meeting with a small army of doctors. I imagined her sitting up in bed, bandages across her chest as she composed cheerful emails to me on the laptop my father had brought to the hospital. I remembered calling home one random spring day and feeling surprised to hear my grandmother’s voice. Why was she in California, not home in Illinois?

“Is everything OK?” I asked.

“Of course! Everything is fine,” she told me.

I felt angry and betrayed when I realized my parents — and even my extended family – had lied to me. And I couldn’t shake the thought that my parents had decided I wasn’t mature or stable enough to cope.

Be honest with your children from the beginning

When parents lie, the underlying message is, “You can’t handle the truth,” says Wendy S. Harpham, M.D., author of “When a Parent has Cancer: A Guide to Caring for Your Children.” Diagnosed with cancer when her children were 1, 3 and 5 years old, Harpham says her perspective as an internal medicine physician guided her decision to be honest from the beginning. “I had patients who, as children, had been lied to and some reacted in very maladaptive ways to signs of illness or having illness,” she says.

While there is a powerful instinct to protect children from upsetting news and the pain it causes, hiding a diagnosis can backfire. “Children’s brains are wired to draw conclusions based on what they see, hear and know,” Harpham says. “If they’re seeing stuff without context, without explanation, they are going to draw conclusions which may be worse than what is the truth.”

In the years following my mother’s illness, I worried constantly about her prognosis, even when she told me everything was going well. And while I’ve always struggled with generalized anxiety, as an adult I’ve found health anxiety is my biggest challenge.

The greatest gift we can give our children is not protection from the world, but the confidence and tools to cope and grow.

How to tell children about a parent’s cancer diagnosis

Since her diagnosis, Harpham has worked to raise awareness among clinicians and patients about the challenges of survivorship, including caring for children when a parent has cancer. When telling children about a serious illness, Harpham advises two steps: First, accept that the illness has entered your life. Second, choose to use the unwanted experience positively.

By being honest, “parents can shape the child’s understanding of what is going on, of what to do. They can guide the child to healthy responses, to a healthy perspective,” she says.

When breaking the news, offer compassion rather than pity. “Compassion is when you help children feel heard and help them through, whereas pity disempowers them,” Harpham says.

Children’s reaction to cancer news can vary widely

Be prepared for any reaction, from an emotional outburst to apparent indifference. On one occasion, Harpham’s daughter stormed out the door after hearing bad news. While painful to witness, such reactions represent a normal, healthy response, Harpham says. They indicate the child understands the significance of what’s happening and feels safe enough to show you they need comfort. Keep in mind that a child who reacts calmly at first may need support later.

Care for children’s needs through communication and planning

Harpham encourages parents to focus on children’s fundamental needs, whether they are toddlers or teenagers. Do children have transportation to school, soccer practice and piano lessons? Do they know they’ll be cared for amid the crisis, even though some household routines are changing?

It’s also important for children to have a basic understanding of the parent’s treatment plan, though the amount of detail will vary depending on the child. If the parent is undergoing chemotherapy, for example, a teenager may want to know more than a first grader, who may just need to understand why mom or dad will be more tired than usual. Harpham recalls that her middle child was fascinated by the X-rays she brought home, while her oldest only wanted to know when her mother would be away for treatment.

Regular communication is critical, not only when parents share a diagnosis, but also later as children continue to cope with its impact. “If there’s open communication, you can see how they’re processing,” Harpham says. Children whose parents have faced cancer are acutely aware that life is fragile, she adds. “If you don’t talk about it, if they just experience the uncertainty and the fragility, it’s a recipe for anxiety.”

Even if adults didn’t tell the truth about an illness from the start, it’s possible to rebuild trust. Harpham suggests that parents explain why they kept the information a secret. Maybe they did what they felt was best in a difficult situation or a spouse or doctor advised them not to share the news. Offering an apology for the harm this caused and asking what children need to move forward, is also a good idea. While nothing can change the past, parents can commit to keeping children in the loop going forward.

Choosing a different path leads to growth, adaptability, confidence

My mother passed away in 2004. While we didn’t discuss the impact of her decision, I’ve never doubted that she loved me and wanted the best for me. But in 2022, when I was diagnosed with breast cancer, I wanted to handle things differently. A few days after my diagnosis, my husband and I sat down to tell our daughters, then 13 and 11 years old. There were tears and hugs as each reacted in her own way.

In that moment, I knew I’d stolen a piece of my children’s innocence, changing their worlds irrevocably. But over time, my daughters have learned to cope with the reality of cancer in their family. My oldest has volunteered for the same breast cancer support organization where I serve as a board member and peer mentor. She talks about becoming a mentor herself one day so she can be a resource for other kids. My youngest raises awareness with her friends about how peer support helps breast cancer survivors.

Today, when my daughters share their fears about developing breast cancer, I tell them I hope they’ll never be diagnosed, but that I understand their worries. We talk about the options they’ll have if needed, from earlier screenings to treatments that we can’t even fathom today.

“The greatest gift we can give our children is not protection from the world, but the confidence and tools to cope and grow,” Harpham says. To the adage, “the truth sets you free,” she adds this caveat, “Even if it hurts when you learn it. Even if it hurts when you share it.”

Posted in: Health & Nutrition

Comment Policy: All viewpoints are welcome, but comments should remain relevant. Personal attacks, profanity, and aggressive behavior are not allowed. No spam, advertising, or promoting of products/services. Please, only use your real name and limit the amount of links submitted in your comment.

You Might Also Like...

Lasting Benefits of Sports for Kids

Parents want their kids to have an active and healthy lifestyle, and many sign them up for sports hoping to help them develop healthy lifelong habits and a love for […]

The North State Goes Back to School

Health, Safety, and Learning Are our kids going back to school this year? That looming question has been on the minds of parents all summer long. With many schools just […]

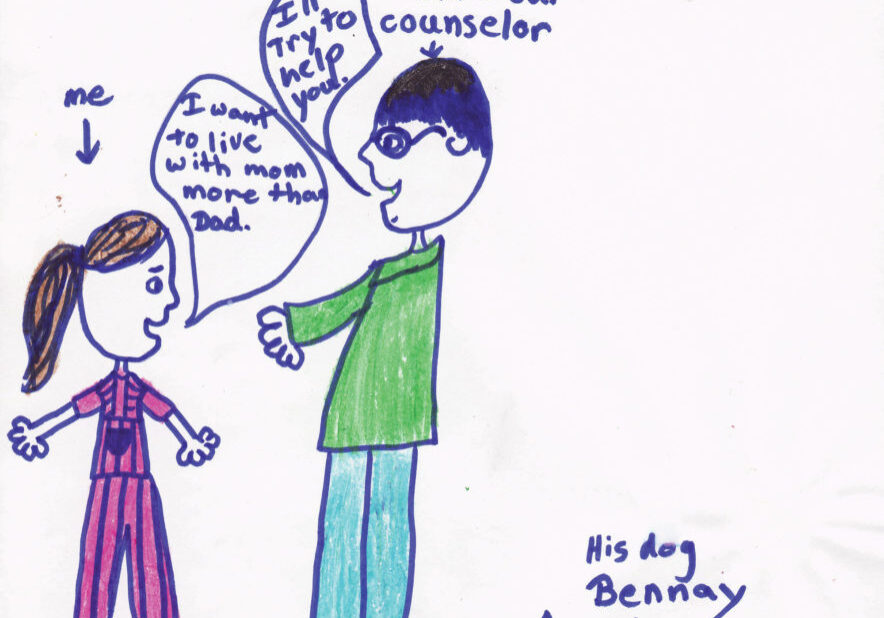

Divorce – How Do We Tell The Kids?

This is one of the most frequent questions we at Kids’ Turn receive from parents starting in the separation or divorce process. It is almost always worded as “How do […]

Reducing Plastic Pollution in the North State

Bottle refill station for famous Mt. Shasta water In October, Mt. Shasta’s Parker Plaza will be home to a new drinking fountain and water bottle refill station. Community members and […]